Universal critical phenomenon discovered in turbulent liquid crystal

Transitions into an absorbing state and directed percolation (DP) universality class

Transitions into an absorbing state, i.e., a state from which a system can never escape once it entered, abound in a wide variety of situations, ranging from spreading of epidemics and fires, to catalytic reactions and calcium dynamics in living cells, etc. Extensive studies have revealed that most numerical models on such absorbing-state transitions share the same critical behavior, constituting the directed percolation (DP) universality class, which is now very well established both in theory and simulations. Nevertheless, no experiment had been able to show fully convincing evidence of this universal behavior despite substantial efforts, being a matter of concern in the literature [A].

Discovery of a DP-class transition

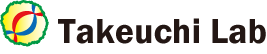

This long-standing puzzle is solved here, in the context of liquid crystal turbulence. We study convection of nematic liquid crystal driven by an electric field, which becomes turbulent when a high voltage is applied. This system has two turbulent states, DSM1 and DSM2, the latter being composed of a high density of topological defects called disclinations. Closely above the threshold voltage, we observe a regime of spatiotemporal intermittency, in which DSM2 patches are moving randomly amid the DSM1 region (Movie 1). Those DSM2 patches disappear at the threshold, reaching the fully DSM1 state, which is absorbing because spontaneous nucleation of disclinations is an essentially unobservable rare event.

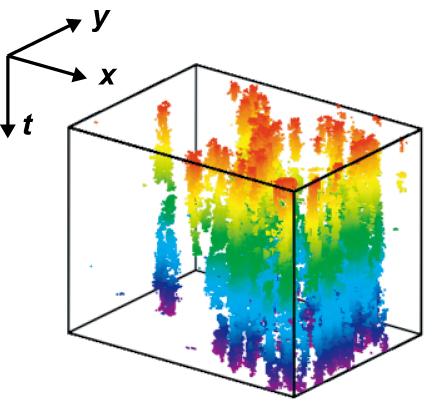

DSM2 patches near criticality evolve as if they "percolate" in the time direction, showing qualitative features expected for the DP-class transitions (Fig. 1). We, therefore, performed experiments which characterize both static and dynamic aspects of critical behavior, measuring a total of 12 critical exponents, 5 scaling functions, and 8 scaling relations, all of which are found in full agreement with those defining the DP class in two spatial dimensions (Fig. 2) [1,2]. This constitutes the first clear and comprehensive experimental evidence of a DP-class transition [B].

Fig. 2: Decay of the DSM2 area fraction $\rho(t)$ (order parameter) when the applied voltage is suddenly decreased to a target voltage. Algebraic decay $\rho(t) \sim t^{-\alpha}$ is found at the critical voltage (red bold line), with exponent $\alpha = 0.48 \pm 0.05$, in agreement with the (2+1)-dimensional DP-class critical exponent $\alpha = 0.45$. Data collapse when both axes are rescaled appropriately, being in agreement with the DP-class universal scaling function obtained numerically (inset). [1,2]

Our experiments showed that DP-class transitions do exist in nature. Indeed, subsequent studies by other groups have shown that DP-class transitions also arise at the onset of turbulence of simple fluids such as water, under shear [C]. From our group, by collaborating with theoreticians, we numerically studied a transition to turbulence in quantum fluids, such as cold atom gas, and showed indications of DP at the transition [3]. As represented by those studies, recent developments have started to report relevance of DP and other kinds of absorbing-state transitions by experiments and realistic models.

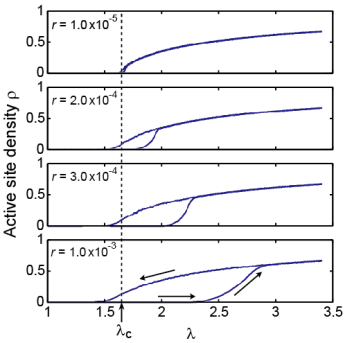

Characteristic hysteresis of absorbing-state phase transitions

Understanding scaling laws governing the critical behavior also serves to explain past experimental observations. For example, the DSM1-DSM2 transition is known to exhibit hysteresis loops when the applied voltage is swept through the critical point (Movie 2). Their width $\Delta V$ depends algebraically on the ramp rate $r$ as $\Delta V \sim r^\kappa$ with $\kappa = 0.5$-$0.6$ [D]. We consider that this hysteresis is due to a very rare spontaneous nucleation of DSM2, and introduced a DP-class model endowed with a rare spontaneous nucleation. This model turned out to show very similar hysteresis loops (Movie 3), for which the hysteresis exponent $\kappa$ agrees with the experimental value (Fig. 3) [4]. Using the standard scaling arguments, we show that the exponent $\kappa$ is linked to the order parameter exponent $\beta'$ via a simple relation, $\kappa = 1/(\beta'+1)$ [4]. This hysteresis is conjectured to be universal in transitions to a quasi-absorbing state, and expected to be a useful tool to characterize absorbing-state transitions in experimental systems, for which observable quantities are usually quite limited.

References

(Takeuchi Lab)

[1] K. A. Takeuchi, M. Kuroda, H. Chaté, and M. Sano, Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 234503 (2007) [pdf, web].

[2] K. A. Takeuchi, M. Kuroda, H. Chaté, and M. Sano, Phys. Rev. E 80, 051116 (2009) [pdf, web].

[3] M. Takahashi, M. Kobayashi, and K. A. Takeuchi, arXiv:1609.01561 [web].

[4] K. A. Takeuchi, Phys. Rev. E 77, 030103(R) (2008) [pdf, web].

(other groups)

[A] H. Hinrichsen, Adv. Phys. 49, 815 (2000) [web]; M. Henkel, H. Hinrichsen, and S. Lübeck, Non-Equilibrium Phase Transitions, Volume I: Absorbing Phase Transitions (Springer, Dordrecht, 2008).

[B] H. Hinrichsen, Physics 2, 96 (2009) [web].

[C] M. Sano and K. Tamai, Nat. Phys. 12, 249 (2016) [web]; G. Lemoult et al., Nat. Phys. 12, 254 (2016) [web].

[D] S. Kai, W. Zimmermann, M. Andoh, and N. Chizumi, Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 1111 (1990) [web].

Main contributors

K. A. Takeuchi