Press releases, web articles, instructional videos, etc.

Mar 21, 2025: press release

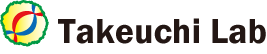

From Order to Chaos: Understanding the Principles Behind Collective Motion in Bacteria

New research reveals how confined bacterial motion shifts from stability to turbulence through distinct transitional phases.

Nov 27, 2024: press release

Researchers uncover what makes large numbers of “squishy” grains start flowing

Such rigidity transitions, from solid-like to fluid-like behavior, are widespread and crucial for biological tissue mechanics. Researchers Samuel Poincloux (currently at Aoyama Gakuin University) and Kazumasa A. Takeuchi of the University of Tokyo have clarified the conditions under which large numbers of “squishy” grains, which can change their shape in response to external forces, transition from acting like a solid to acting like a liquid. Similar transitions occur in many biological processes, including the development of an embryo: cells are “squishy” biological “grains” that form solid tissues and sometimes flow to form different organs. Thus, the experimental and theoretical framework elaborated here will help separate the roles of mechanical and biochemical processes, a critical challenge in biology. The findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

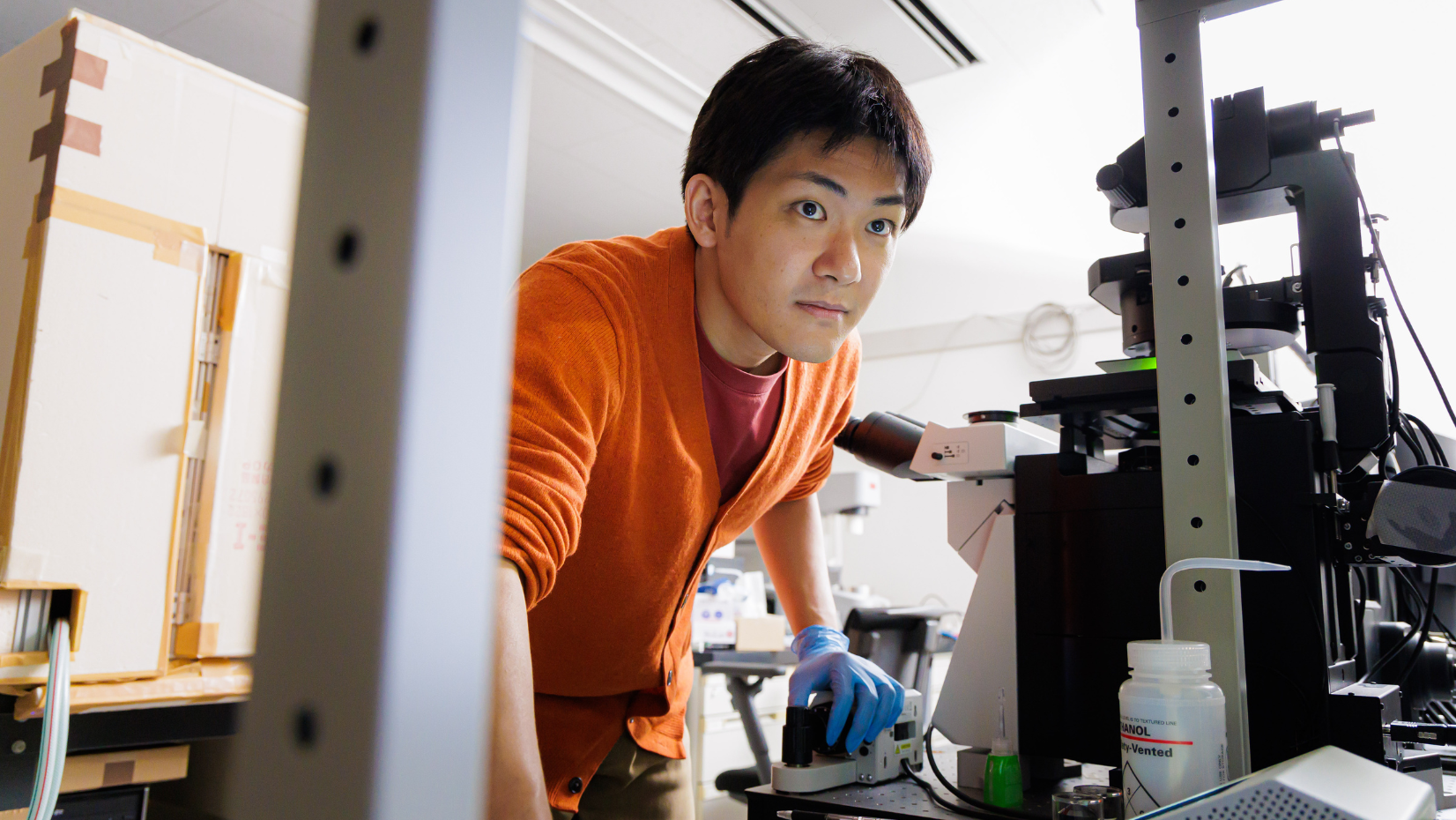

July 20, 2024: interview article (Daiki Nishiguchi)

“Flocks” open up a new world of physics

Daiki Nishiguchi (Assistant Professor, Department of Physics) B.Sc. in Physics, University of Tokyo, March 2012; Ph.D. in Physics, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo, 2017; Research activities as postdoctoral fellow at Institut Pasteur, France, 2017-2019; Assistant Professor, Department of Physics, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo, 2019-Present. 2020 The 14th Young Scientist Award of the Physical Society of Japan.

July 11, 2024: press release

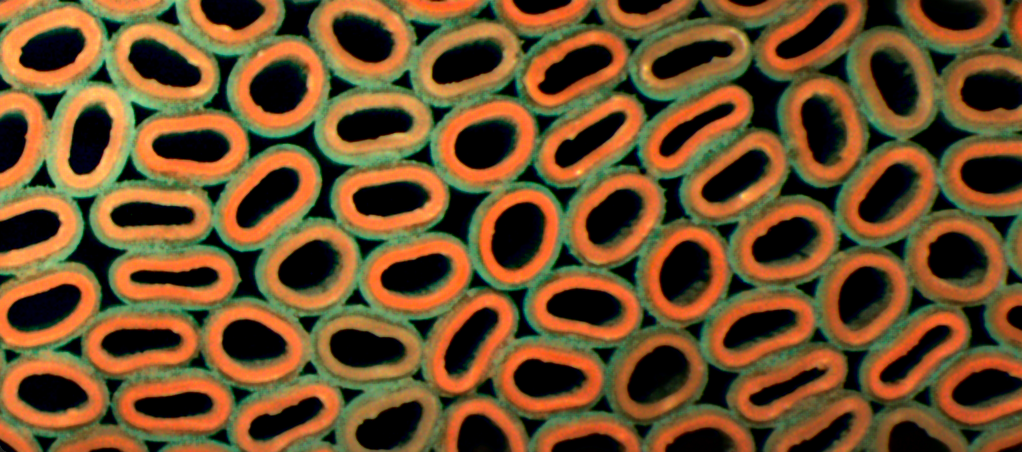

Bacteria form glasslike state: Densely packed E. coli form an immobile material similar to colloidal glass

Dense E. coli bacteria have several similar qualities to colloidal glass, according to new research at the University of Tokyo. Colloids are substances made up of small particles suspended within a fluid, like ink for example. When these particles become higher in density and more packed together, they form a “glassy state.” When researchers multiplied E. coli bacteria within a confined area, they found that they exhibited similar characteristics. More surprisingly, they also showed some other unique properties not typically found in glass-state materials. This study contributes to our understanding of glassy “active matter,” a relatively new field of materials research which crosses physics and life science. In the long term, the researchers hope that these results will contribute to developing materials with new functional capabilities, as well as aiding our understanding of biofilms (where microorganisms stick together to form layers on surfaces) and natural bacterial colonies.

July 3, 2023: interview article (Daiki Nishiguchi)

Searching for universal laws behind the beauty of collective behavior

What is active matter physics? A flock of starlings circling the dusk sky like a gigantic black ghost. Or a school of sardines creating massive whirlpools in the sea to fool their enemies. Or, on land rather than at sea, a colony of army ants marching in circles to form a hill-like structure. All of these examples display magnificent collective behavior as if there was a leader somewhere in control. However, there is no leader, no choreographer. How is such neatly ordered collective behavior possible? That is the mystery that Daiki Nishiguchi is tackling. One could be forgiven for thinking that his research pertains to biology and has nothing to do with physics. Yet, “This is active matter physics, a field within non-equilibrium statistical physics,” he clarifies.

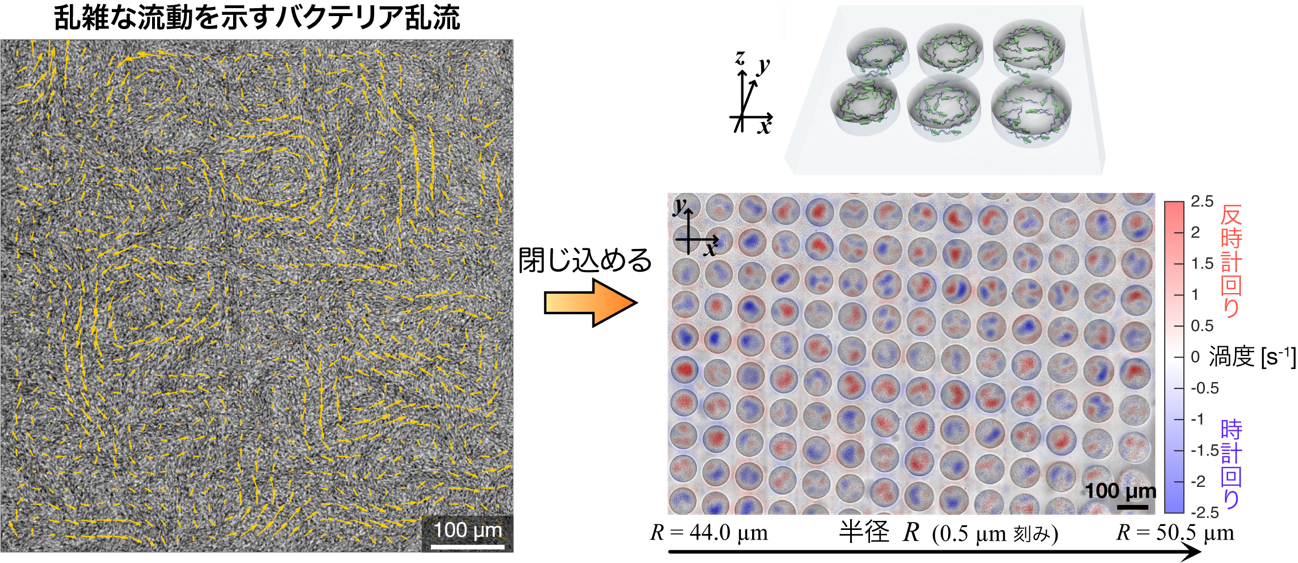

Dec 21, 2022: press release

Microbial 'Jenga' : how bacteria stack

Colonies of rod-shaped bacteria such as Escherichia coli often form dense aggregates called biofilm. Think dental plaques and slimy films on your kitchen sink. Biofilms can cause various problems in medicine (e.g., bacterial infection) and industries (e.g., corrosion). Under a powerful microscope, the bacteria look like strokes in van Gogh's paintings. When their population density is high, they form three-dimensional structures. Takuro Shimaya and Kazumasa Takeuchi from the University of Tokyo show that the way the growing but immotile bacterial cells align with each other helps form three-dimensional structures. The findings offer insights into the physics of their dynamics.